While Beer Twitter occasionally likes to lament that ‘IPA’ has become something of a generic for ‘craft beer’ (whatever that might mean), I’ve been mulling over how we got here. Not so very long ago, IPAs barely registered a blip on the beer radar, even for old-school nerds. My early memories of ‘microbrew’ – and then ‘craft’ – drinking in a pre-Untappd world were very much tied to bitters, pale ales, stouts, porters and a broad ‘Belgian’ category. As memory is very much an unreliable narrarator, I had a look back at my library to see if the beer spectrum I remembered from the late 1990s/early 2000s was, in fact, reasonably accurate.

While Beer Twitter occasionally likes to lament that ‘IPA’ has become something of a generic for ‘craft beer’ (whatever that might mean), I’ve been mulling over how we got here. Not so very long ago, IPAs barely registered a blip on the beer radar, even for old-school nerds. My early memories of ‘microbrew’ – and then ‘craft’ – drinking in a pre-Untappd world were very much tied to bitters, pale ales, stouts, porters and a broad ‘Belgian’ category. As memory is very much an unreliable narrarator, I had a look back at my library to see if the beer spectrum I remembered from the late 1990s/early 2000s was, in fact, reasonably accurate.

Dipping into The Beer Enthusiast’s Guide by Gregg Smith (1994), there are a number of German and Belgian styles bucketed together, with what we can broadly call English styles listed out more specifically: pale ales, brown ales, porter, stout and strong ale. IPA doesn’t get a mention in the main table of contents at all. Digging into the details, we *do* see IPA as a sub-category of pale ales, along with bitters, and English and American pale ales. Commercial examples aren’t given for each sub-type, but we do get listings for those two – English pale ales name-checked are Worthington White Shield, Samuel Smith’s and Bass. For the Americans, Sierra Nevada (natch) and Red Hook are the standard-bearers. But what I find most interesting in this book are the hops called out for IPAs (‘…a classic style born of necessity’ – all you mythbusters already know the story here, please go read Martyn Cornell and Ron Pattinson like sensible people): Goldings, Galena and Brewers Gold for bittering, and Fuggles, Cascade and Tettnang for aroma. I suspect it would be difficult to find even English IPAs primarily made with these hops nowadays, barring a few holdouts – and I also doubt the commercial examples are still using exclusively their recipes from the 1990s. It’s certainly an interesting list: Anchor Liberty Ale, Sierra Nevada Celebration Ale, Young’s Special London Ale and Ballantine’s Old India Pale Ale.

Even checking a homebrew book from the same year, Homebrew Favorites, by Karl F. Lutzen and Mark Stevens, has a very brief IPA section, and the beers – mostly Anchor Liberty clones – rely heavily on Fuggles and East Kent Goldings. Fast-forward to 2007 and Brewing Classic Styles, by Jamil Zainasheff and John J. Palmer (of How to Brew fame), and we see a very clear distinction between English and American IPAs – English IPAs are ‘…hoppy, moderately strong’ pale ales, while American IPAs are ‘…decidedly hoppy and bitter.’ The English IPAs still feature Fuggles and East Kent Goldings, while their American cousins are loaded with Horizon, Centennial, Centennial, Simcoe and Amarillo.

So, what changed between 1994 and 2007? In 1999, Terry Foster wrote in his volume Pale Ale: ‘…American micros are generally to be commended for their return to traditional values in pale ale brewing, particularly regarding their approach to producing beers of high hop bitterness and character.’ And this passage stands out:

‘But, why is bitter the predominant style? Why not pale ale? Why not IPA? As I said at the opening of this section, even the concept of what an IPA should be seems to have been forgotten by the few English brewers who still turn out beers under this name. Brewers seemed to use the name pale and and allowed the name IPA to lapse, just as the East India export trade itself was retrenched. Competition from lagers, as well as outside influences such as Prohibition in America, resulted in the name no longer having the cachet it once had.’ – p. 65

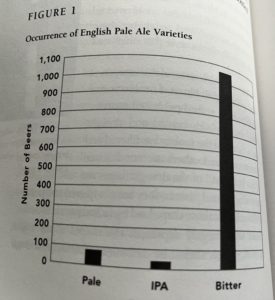

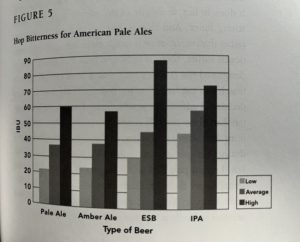

However, Foster also notes the 1994 British Guild of Beer Writers IPA conference, where there was a take on an 18th century IPA brewed, for science (‘intensely bitter’). And later in the book, he points out that American beers are trending hoppier and more bitter overall – I found this graph (as well as the other showing IPAs in the UK – apologies for the terrible image quality) showing American ESBs as hoppier than IPAs fascinating, though perhaps some context is provided by this note: ‘Bert Grant’s ‘original’ IPA is said to have 60 IBU. In general, levels of 50-55 IBU are not rare, and Anderson Valley claims that its Hop Ottin IPA has as much as 90 IBU!’ (emphasis Foster’s). He also singles out Cascades specifically, which makes sense – try to imagine a West Coast IPA without Cascades nowadays.

|

|

And speaking of the Pacific Northwest, by 1999’s Buying Guide to Beer (ed. Marc Dornan), we see that ‘…US craft brewers have claimed the style as their own, and often brew IPAs with assertive Pacific Northwest hop varieties that give them a hugely aromatic hop accent.’ Brands given plaudits include Full Sail IPA and BridgePort IPA (RIP), as well as Fullers IPA.

Moving on, the 7th ed of Michael Jackson’s Pocket Guide to Beer from 2000 recognizes American IPAs, but still highlights relatively few of them – still, many more than in his Great Beer Guide (my edition also 2000 – it takes a lot of leafing through to find an IPA).

My very, very uninformed assumption is that the IBU (and, eventually, ABV) arms race among (mostly) American IPAs of the early-to-mid 2000s was tied directly to the new (and now common) varieties of hops developed in that era…and that the eventual rise of hazy and milkshake IPAs was the direct response to the bitter and HARDCORE era that preceded it (though let’s all pour one out for brut IPAs and their hot second in the spotlight). Someone much more knowledgeable than I am has no doubt worked through the chicken-or-egg driver in that relationship…though my point here was less to determine the ‘why’ and more to confirm that my hazy (har) memory was correct – IPAs were Unusual, once upon a time.

Perhaps Randy Mosher summed up the versatility best in his 2004 book, Radical Brewing:

‘As a platform for improvisation, IPA is a pretty good one. It’s a simple concept – a pale, subtly malty base, not quite overwhelmed by fresh hops. Such an idea is robust and timeless. No wonder it has satisfied the discriminating beer drinker for a couple of hundred years now.’

I’m not sure he meant milkshake IPAs, but hey, why not? More importantly, what comes next? And can we have more ESBs and brown ales again, please?

2 thoughts on “Musings on the Inevitable(?) Resurrection & Generification of IPA”